I think it important to try to see the present calamity in a true perspective, CS Lewis said in a speech to Oxford University students at the eve of World War II in 1939. The war creates no absolutely new situation: it simply aggravates the permanent human situation so that we can no longer ignore it. Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice. Human culture has always had to exist under the shadow of something infinitely more important than itself…

Even those periods which we think most tranquil, like the nineteenth century, turn out, on closer inspection, to be full of crises, alarms, difficulties, emergencies.

We are mistaken when we compare war with “normal life.” Life has never been normal...

12 years after CS Lewis delivered this address, after the earth was stained by the deadliest genocide and military conflict in history, resulting in a full-fledged 3% reduction of the world population, writer Czeslaw Milosz defected from Stalinist Poland and soon thereafter published The Captivate Mind, a fascinating probe on the psychological allure of Stalinism and communism writ large.

Milosz compares the (purported) harmonious unity offered by communism to the “Murti-Bing pill” depicted by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz in his 1930 speculative novel Insatiability. Similar to the “Soma” drug illustrated by Aldous Huxley two years later in Brave New World, the Murti-Bing pill makes man “serene and happy,” numbing discomfort and rendering his problems “superficial and unimportant.”

Of course man’s life becomes devoid of purpose and meaning in a perpetual state of artificial tranquility, as writers and philosophers as varied as Heschel and Orwell have made clear. But in this short essay I don’t want to talk about the impulse of man to escape the emotional vicissitudes of his existence for eternal neutrality, an instinct to which the weak have capitulated since the dawn of creation and to which man will continue to capitulate as long as humans remain capable of greatness, a phenomenon which evolves through the centuries only by method of escape and never in essence.

Instead I want to cultivate perspective on war, on this war, which, to many of us, even Israelis, seems strange and unordinary.

Man tends to regard the order he lives in as natural, Milosz writes in The Captive Mind. The houses he passes on his way to work seem more like rocks rising out of the earth than like products of human hands…The clothes he wears are exactly what they should be, and he laughs at the idea that he might equally well be wearing a Roman toga or medieval armor.

He respects and envies a minister of state or a bank director, and regards the possession of a considerable amount of money as the main guarantee of peace and security. He cannot believe that one day a rider may appear on a street he knows well, where cats sleep and children play, and start catching passers-by with his lasso...

His first stroll along a street littered with glass from bomb-shattered windows shakes his faith in the “natural-ness” of the world…Father down the street, he stops before a house split in half by a bomb, the privacy of people’s homes—the family smells, the warmth of the beehive life, the furniture preserving the memory of loves and hatreds—cut open to public view. [Sounds like Be’eri...]

Which world is “natural”? That which existed before, or the world of war? Both are natural, if both are within the realm of one’s experience. All the concepts men live by are a product of the historic formation in which they find themselves [a perspective you might take trouble with if you are a God-fearing Jew but nonetheless carrying some truth…]

And peering towards the West: The man of [the Soviet Union] cannot take Americans seriously because they have never undergone the experiences that teach men how relative their judgements and thinking habits are. Their resultant lack of imagination is appalling. Because they were born and raised in a given social order and in a given system of values, they believe that any other order must be “unnatural,” and that it cannot last because it is incompatible with human nature.

I’ll come up for air here as Milosz continues to take swings at the ignoramus American who fails to understand not necessarily the depths of evil but its possible manifestations by the cruelty of man in this world, a phenomenon still present as many Westerners continue to shrug in incredulity at the horrors of October 7 to maintain pleasant worldviews about the goodness of man and moral equality of cultures.

Because once we realize that change is the only constant and no situation—however long-lasting—is “normal” or “natural,” we need to decide what to do in that uncomfortable state. Perhaps the most urgent question, as CS Lewis said in 1939, is how to sustain the pursuit of truth, beauty and wisdom, when so many of us, our soldiers and security personnel, are preserving the more fundamental needs of our people, the lowest-tier of Maslow’s hierarchy, our very safety?

Let me share with you a Facebook post from my uncle Tal three weeks ago:

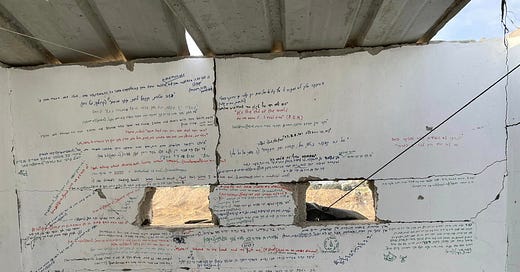

If you ever go to Khan Yunis, to the eastern suburbs, you will find a half-house on the remains of a street, just above a shield that belonged to a battalion whose name I cannot say, and there, on the remaining third floor of the building, of which there were probably eight, there is a wall. In the wall are two block-sized holes, cut for the guards at the post to have a hidden lookout to the west.

This wall, eight feet high, with cracks down the white paint, is full of song. Each guard, in turn, writes down a line or two of a song or poem he likes, as a note, as an inspiration, for the guards to follow.

There are many acts of war, he continues. Everyone already knows about the projectiles and ammunition, the tanks and artillery. But there is also culture. [The Israeli army] also brings culture. The Romans brought baths and paved roads. We bring songs and guitars.

I teared up when I read this post, in utter awe and admiration of our IDF heroes and our commitment to culture even in the dark pits of war.

It got me thinking of the continuation of Lewis’ address, where he says that plausible reasons have never been lacking for putting off all merely cultural activities until some imminent danger has been averted or some crying injustice put right. But humanity long ago chose to neglect those plausible reasons. They wanted knowledge and beauty now, and would not wait for the suitable moment that never comes.

As many of you probably saw on LinkedIn, I just returned from 3 weeks in the states. During my first 24 hours, and even now—4 days later—I can’t stop smiling. People probably think I’m crazy, I wrote on LinkedIn. So crazy that when I went into my friend’s office earlier this week on Rothschild Blvd, he couldn’t help but ask: Are you okay, Andrew?

Did you hear? I said with glowing eyes. The Jews built a state. A flourishing state. A gorgeous state. Did you hear? It was pouring rain. Thunder cracked in the sky. And yet among the wet streets of Tel Aviv I felt home, swelling in awe at the miracle that lay before our eyes.

My friend looked at me like I was delusional. But he understood. You seemed like plant without sunshine in America, he said. Now you’re in the sunshine.

What happened?

Here’s what I think — it was the Bias towards Action I missed - living around a nation of heroes and doers, courageously and optimistically putting one step in front of another. It’s this bias towards action, rather than succumbing to fear, that is so electric, so palpable, so contagious. Israelis are so busy living, building, growing, they don’t have time to worry, or at least not in the same way I saw in America.

And that’s beautiful because (I’m only realizing this now as I write) action cures fear. The Israeli people sprung into action after Oct. 7 because they know this instinctively, we know this instinctively. Action cures fear. (It also saves lives.)

Yes our reality is...scary and unstable. There are still 132 hostages held by Hamas. Our soldiers are dying almost every day. Hezbollah in the North...the list goes on.

This reality is not for the faint of heart, but here’s what’s remarkable: if you walk around Tel Aviv or Jerusalem, you probably won’t know there’s a war. There are hints: guns and hostage posters, some people on edge. But mostly Israelis continue to put one foot in front of the other, just like they know best.

The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, said Theodore Roosevelt famously, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly…

That’s the point of this essay: to have perspective on the war so we can continue to strive valiantly, whether we’re guarding or babysitting, programming or designing, praying or learning or really just living.

I have put before you life and death, blessing and curse, God tells the People of Israel. Choose life. Even continuing to live is striving valiantly. May God be with us.

Thank you for seeing the big picture and keeping things in perspective.

The "bias towards action" is a great insight. Different than "industrious", which the Jews have always been, the "action" of Israelis carries the sense of a people in charge of their own destiny. It is empowering.

Beautiful and thoughtful piece that highlights the essence of life here in contrast to America; striving to act and do as opposed to just being. Thank you, Andrew.